The old Hajj routes and the legend of Zubaydah

“We moved out to the Bottom of Marr with an innumerable host of pilgrims from Iraq, Khurasan, Fars and other eastern lands, so many that the earth surged with them like the sea and their march resembled the movement of a high-piled cloud…With this caravan there were many draught camels for supplying the poorer pilgrims with water, and other camels to carry the provisions issued as alms and the medicines, potions, and sugar required for any who fell ill. Whenever the caravan halted food was cooked in great brass cauldrons, and from these the needs of the poorer pilgrims and those who had no provisions were supplied. A number of spare camels accompanied it to carry those who were unable to walk…” —From The Travels of Ibn Battuta (A.D 1325-1354)

The journey to perform one of the pillars of Islam— the annual pilgrimage of Hajj— was once a great undertaking, with its unpaved rocky sandy roads riddled with danger from scorching relentless heat, possible raids by highwaymen, and unpredictable great risks of illness and disease. Millions of pilgrims took part, and continue to take part in this great spiritual and emotional journey of great joy and happiness, longing and anticipation, exhaustion and serenity. No obstacles can hinder the determination and the dedication of the faithful, for it took the widely celebrated 14th century Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta over 18 difficult months to finally reach Makkah to perform Hajj after leaving his hometown of Tangier at the age of 21.

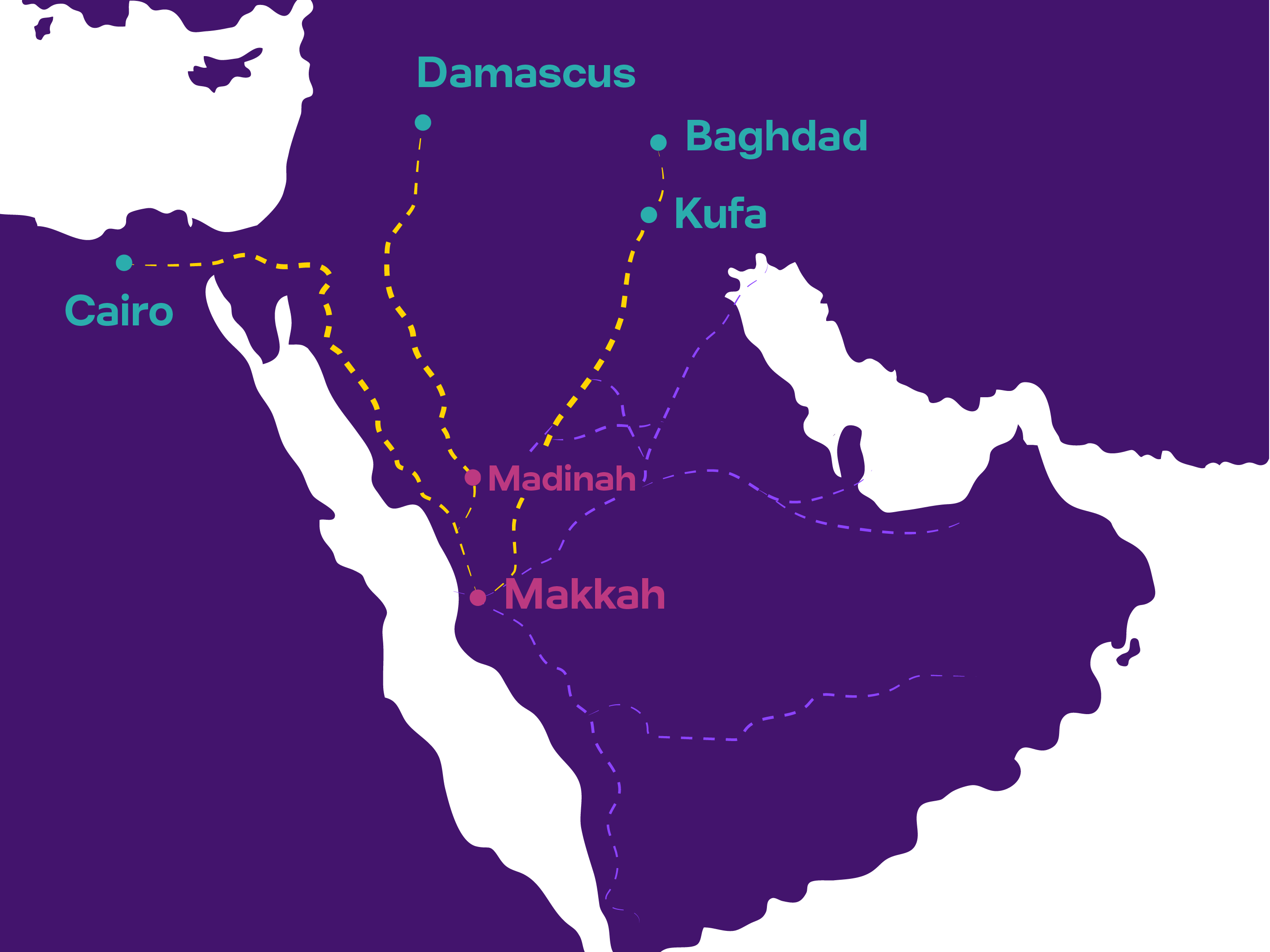

In the past, pilgrims would arrive to the holy city of Makkah on foot, crossing the unforgiving desert in camel caravans and on donkeys. Until the 19th century, there were three main caravans to Makkah, which were one of the world’s first transcontinental, cross, and intercultural routes. The Egyptian caravan set out from Cairo, crossed the Sinai Peninsula, and then followed the coastal plain of western Arabia to Makkah, a difficult journey that took 35 to 40 days. The other great caravan assembled in Damascus, Syria, and moved south via Madinah, reaching Makkah in about 30 days. After the capture of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks in 1453, this caravan began in Istanbul, gathered pilgrims from throughout Asia Minor along the way, and then proceeded to Makkah from Damascus. The third major caravan crossed the Peninsula from Baghdad, Iraq.

Designed By Samah Alhamdan

Designed By Samah Alhamdan

With the onset of modern transportation, the sea of white worshippers began to arrive on buses and on ships from far-flung parts of the Muslim world. Then came the planes, and the cars on safer roads built for the faithful to arrive and perform this life-changing ritual, required at least once in a lifetime for a Muslim, if able.

Throughout history, there have been many figures who have lent their hand to assist and change the landscape of pilgrimage, which include building aflaj (water channels) to special pilgrim accommodations to various acts of charity. One such legendary figure is Zubaydah bint Abu Ja‘far al-Mansur (766-831). A noblewoman of great philanthropy and a patron of arts and poetry, her grandfather was the Abbasid Caliph Abu Ja‘far al-Mansur (the second Abbasid Caliph), and her husband was the famous Caliph Harun al-Rashid (the fifth Abbasid Caliph). Zubaydah’s name was Amatul Aziz, and it was her grandfather, al-Mansur, who gave her the nickname “Zubaydah,” which means “Little Butter Ball” “on account of her plumpness” as a child, according to the 13th-century biographer Ibn Khalikhan.

Legends state that during her own pilgrimage from Kufa, Iraq, to Makkah, she witnessed the struggles of pilgrims along this difficult road, and decided to alleviate the hardships and the expenses endured by pilgrims by building support systems along the way. Zubaydah initiated the historic project to build service stations with multiple water wells all along the pilgrimage route from Baghdad to Makkah. Darb Zubaydah (The route/trail of Zubaydah) was therefore developed to include wells, pools, dams, palaces, rest houses, and pavement. Her project included 27 major stations and 27 substations, and the most prominent among them are: Al-Sheihiyat, Al-Jumaima, Faid, Rabadha, That-Erq, and Khuraba.

The origin of this pilgrimage route dates back to the pre-Islamic era, but its importance significantly increased with the dawn of Islam. Historic sources report that by the end of the year (12 AH/early 634 AD) the legendary Muslim commander Khalid Ibn Al-Walid returned from Iraq to perform Hajj, reaching That-Erq in less than two weeks, using this route that was then the shortest distance.

During the time of the early caliphates, the route flourished and reached its zenith and prosperity during the Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258). It was initiated and constructed by Abul Abbas Al-Saffah, the first Abbasid Caliph in 751, and was known at that time as “Darb Heerah.” He ordered the establishment of milestones, flags, and lighthouses along the trail from Kufa to Makkah in order to facilitate the trip of pilgrims and merchants.

But as history has shown, the great efforts of Zubaydah to undertake this massive upgrading project to ease the dangerous trip to Makkah was so remarkable that the route was renamed from Darb Heerah to Darb Zubaydah and still carries her name until today.

This special route was submitted in 2015 to UNESCO by Saudi Arabia, and is on The Tentative Lists of States Parties.

“Zubaydah road perfectly embodies the cultural significance coming from exchanges and multi-dimensional dialogue across countries as it permitted to bring together Muslim pilgrims from different ethnic groups and regions, creating the cultural, religious and scientific exchanges among the people of various parts of the world,” states the submission.

“Zubaydah road illustrates the interaction of movement, along the route, in space and time from the pre-Islamic period to the end of the Abbasid Caliphate in the 13th century CE.”

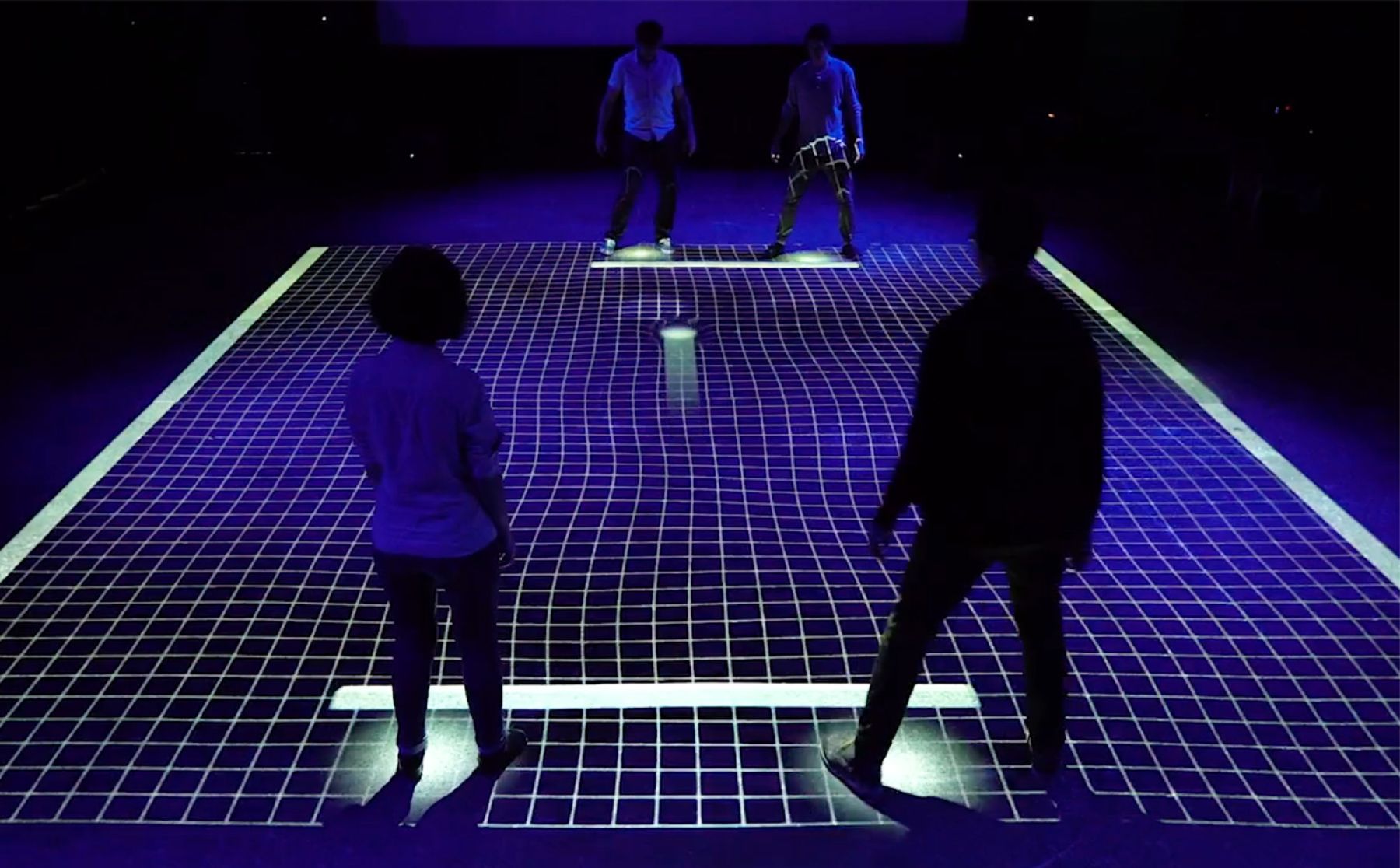

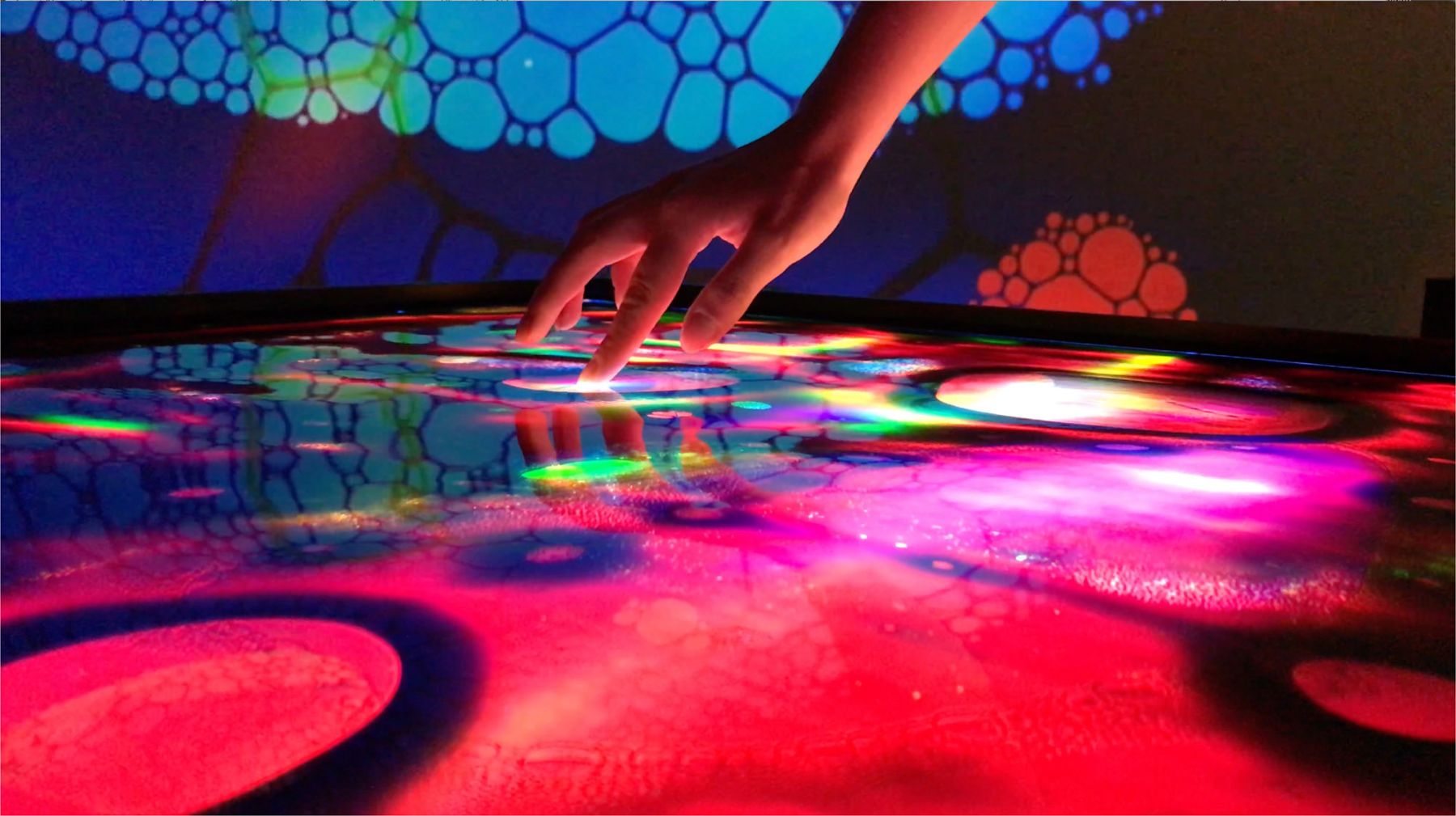

And at Ithra, a center celebrating Saudi and world cultures will pay homage to Darb Zubaydah and the importance of Hajj routes during its celebration of Eid Al-Adha programs. For beyond the various physical routes our lives take us on, some pleasant, some not, there are those internal routes of discovery, that continue to awe and inspire us, as we embrace our culture, and grow and understand our story and other cultures and their artistic expressions, as presented at Ithra, and beyond.

Written by Rym Tina Al-Ghazal