Direction of Light: An Ithra Interview with L.A. artist Darel Carey

“We are slowly pouring our consciousnesses into the clouds.”

Darel Carey

In June 2021, the Los Angeles-based artist Darel Carey came to the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture, Ithra, in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia to make a site-specific work titled “Direction of Light” in conjunction with the exhibition “Seeing & Perceiving.” Carey took his black-tape approach to the unusually long, freestanding and internally-lighted white escalator in the center of the Ithra Plaza that rises without external structural supports through open space to the third floor of the Ithra Library. Carey’s black tape intervention appears as straight-line stripes that create curves and spatial effects through their systematized differences of length and direction. Carey sat down to talk with Ithra while he was taking a break from the nearly completed project on June 17, 2021.

Ithra: How did you start working with tape – was it through using it to mask off paintings?

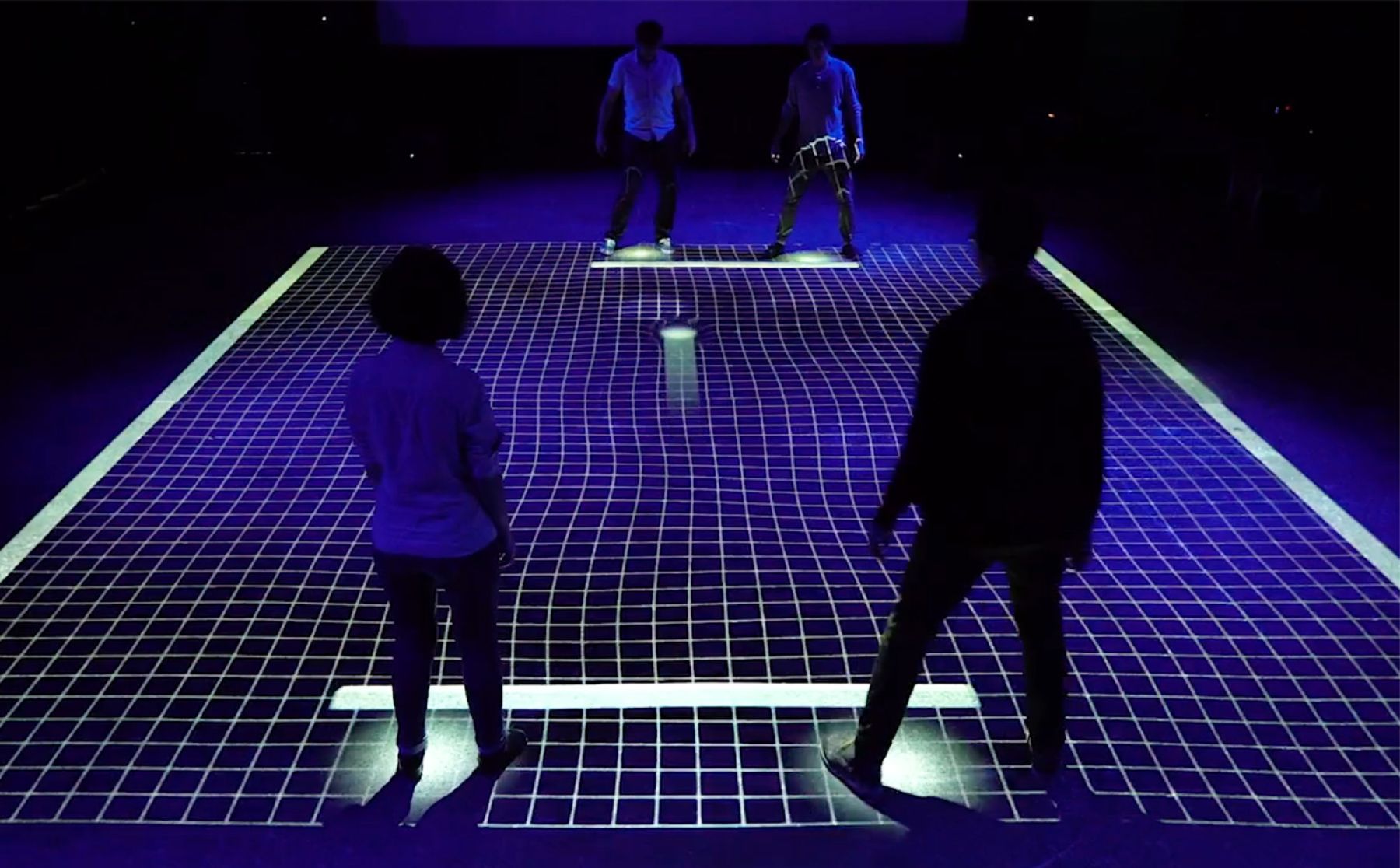

DC: During my senior year at Otis College, our studio group put together a show in the school gallery. We came up with the idea of gridding up the entire gallery and placing our artwork in and on the grid. I ended up doing most of the gridding using black masking tape. While I was taping onto the walls and the floor, a question crossed my mind. In art, tape is usually used as a part of the process, as a means to an end – usually to mask off where you don’t want your paint to go. I began to wonder: Why couldn’t I use tape as a medium in itself? The purpose of the tape grid was as a background to our art, and once the show was over we would take the tape off. So, if tape could be used as a background, serve its purpose, and then be easily removed from the floor and walls, why couldn’t an art installation be in the form of tape, serve its purpose, and then be easily removed? I initially wanted to paint a large immersive piece on the wall and possibly onto the floor, but it would be difficult to remove from the floor. With tape, I could get the same results with no consequence. Limits of scale and location were removed, and this intrigued me.

My installation for that show was an anamorphic, cubic formation in the corner of the gallery. But later I found more uses for tape. I combined it with my line drawings, which were actually very curvy and wavy. I liked to draw organically, in a natural, intuitive way, setting up simple rules for myself. Using a ruler to make straight lines took away the intuition (and fun) for me. With tape, I was suddenly in a situation where I could intuitively use straight lines to draw instead of curvy ones, so I was able to do something organic with something rigid, which was new to me, and an exciting realm of discovery.

Ithra: Do you think of your work as painting?

DC: I think of my work more as drawing than painting, because with my line work, before I was using tape, I was drawing. I used pencils, pens, markers, and even when I used a paint brush or spray paint, I was “drawing” lines with them.

Ithra: How would you relate your work to Op artists like Viktor Vasarely or Bridget Riley as opposed to fanciful illusionists like MC Escher?

DC: I feel like my work is somewhere in between. I see a relationship of my work to Vasarely and Riley in an optical sense. Similarities with our works include placements and juxtapositions of colors or black and white and how those arrangements affect your vision. Optical art is abstract, and it takes our eyes to the edge of their perception, breaking down how we perceive into its simplest forms. It gets down to the bottom of how our eyes decide what they’re looking at.

Escher’s work is representative, but the illusions lie in presenting two contradictory truths in the same place, and you can only believe one of them at a time. While Op Art makes you think about how you see, Escher’s illusions make you think about how you think about what you see. It’s also perception on a more spatial level. Although my work is abstract, this relates because, with my lines, I dimensionalize a flat surface or superimpose a new set of perceived dimensions onto the ones that are already there. Depending on where you’re looking from, you may see the same form as concave or convex. Like Escher’s illusions, both are true, in as much as you can perceive them, depending on your perspective at the time.

Ithra: What do you think about Dazzle Camouflage?

DC: It can be deceiving, so I can see how it relates to my work. When I dimensionalize a space or a room, the viewer may have a difficult time discerning where the corners are, or how far the walls are, etc. That was the point of Dazzle camouflage – to make distance and speed difficult to calculate so it was harder to target the ships.

Ithra: Do you see a difference between optical and spatial perception? What roles do they play in your work?

DC: Yes, I do see a difference between optical and spatial perception. To me, they both overlap, but spatial perception doesn’t necessarily have to be optical, and optical perception doesn’t have to be spatial. Optical perception addresses how you see, and spatial perception addresses how you discern things in relation to one another in space. I think of my work as belonging to a subset of Op Art, or as a hybrid of optical and spatial perception. As an Op artist, I find that my work doesn’t relate to all of what Op Art is. Things like uniform patterns and rigid repetition may share some optical effects with my work, but a large part of my interest is in the perception of space and illusion.

Most of my work is large-scale and immersive, and spatial perception plays a big role here. The experiencer can walk around my work, look at it from different angles, and look at it while moving. All of these things have particular effects on perception that are spatial in nature. But, of course, there are the ever-present optical effects, so I can’t separate the two. My work is both.

Ithra: There is a physicality to your execution; does this play a content role in your work?

DC: It does, in the aspect of my process. In art, sometimes how something is created isn’t as significant as what it is or what it means. But with my work, how it is created plays a significant role. I start off with a system of simple rules, and build up the piece organically. When I approach a space and start working, I look at the big-picture and pay attention to the details, and everything in between works itself out. By the time I begin with my big-picture idea in mind, I’m steeped in the details, and I’m never sure exactly how a piece is going to turn out. I’m only familiar with the process, so it’s always a dialogue between me and the lines. The more installations I create, the more I understand the process, and can guide the direction of the lines to an extent.

Ithra: How would you describe the content of your work? What, for example, are you trying to achieve with “Direction of Light”?

DC: With the title, “Direction of Light,” when I was imagining the creation, I thought of the escalator as a beam of light, with the dimensional lines partitioning the segments of light like slices of time. Just as each line is one step in the evolution of the final form, each segment in between each line is one step in the timeline of light. My work tends to have a visually kinetic flow, and with this particular form it made me think of seeing the light move, one time slice at a time, down the beam, in hyper slow-motion of course.

As far as what I hope to achieve, I hope it causes people to think about what they see, and wonder about how they perceive.

Ithra: Is there a street art element to your work, such as the specificity of the site?

DC: I do have a background in street art. In my teens I was into graffiti, and even then, I was interested in illusion. I would create shaded, intertwined block letters that looked like they were popping out of the wall. With my work now as well, location can play a big role. It doesn’t always have to… I could, for example, do fine with a blank flat surface. But a lot of the intrigue in my work comes from the invasion of a space or a corner. I superimpose the illusion of volume or topography onto a space, and sometimes with a specific vantage point as well.

Ithra: Where can the interested members of the public check out your work? Do you have gallery representation?

DC: I’m not represented by a gallery. Sometimes I’ll be approached by a gallery for a particular event or exhibition.

As far as buying a piece, right now, for the past few years, I’ve been creating tape installations and painting murals. I haven’t done any hanging pieces in a while. I think it’s because of the scale and immersive nature of my work, that it doesn’t feel as suitable to work in the smaller range. But I don’t know, I may start experimenting with that soon.

Due to the ephemeral nature of my tape installations, a lot of them are gone and only live on digitally. I have some murals up, though. One at my alma mater, Otis College. The best way to see where I have work is to follow me on Instagram (@darelCarey). That is the most up-to-date platform to see what I’m doing and what I have coming up.

Ithra: Your statements and work point toward the notion of Emergent Properties – where properties that are not in the constituent parts emerge with the broader perception of the whole. What role does that play in your work?

DC: The idea of emergence plays a big role in my philosophy and my art. I’m fascinated by emergent properties and the process of simple things becoming complex. I began to really understand this as I continued to make more and more work. I started to understand more about what was going on with the lines in relation to one another. With a system of consistency and gradual change, natural patterns form. A line on its own is just a line. And the line next to that line is also just a line. But if you zoom out and look at all of the lines together, they form something greater than the sum of its parts. There is form and curvature. Even though all of the lines are straight, the way they are arranged creates a perceived curvature. In a way, the curves aren’t really there. But on another level, they are there. The individual lines don’t know (if a line could know) that they are part of these curves and forms. They only see themselves as straight lines next to other straight lines. This is the way everything in the universe emerges. The cells in our bodies don’t know they are part of our bodies. They live in their own cellular universes. And before we knew about cells, we had no idea we were complex combinations of cells. And yet, here we are. From atoms, to stars, to elements, to cells, to bodies, to minds, and beyond: complex things are just an arrangement of simple things.

Ithra: You have an apparent proclivity for natural patterns, but your work seems primarily geared towards perceptual psychology. Is that accurate? And are you concerned with consciousness and/or AI?

DC: I try to tie in my philosophy with my work as much as it makes sense to do so. On the surface level, my work addresses perceptual psychology. On a deeper level, in a philosophical way, my work is analogous to natural patterns, and I think the perception and psychology are embedded in grander natural patterns. I’d say my work is a natural pattern, as I see art as an extension of human creativity, which is an extension of consciousness, which is an extension of basic survival mechanisms, and all of these are natural. I don’t see a separation between “natural” and “manmade.” You can make a distinction, but to say manmade isn’t natural is saying the only evolution there is, is biological evolution. Biological

evolution is just one stage of evolution. Our cultures evolve, our societies evolve, our technologies evolve. These are just different levels of evolution that emerged from biological evolution. To my understanding, consciousness is an amazing emergent phenomenon, something intangible that emerged from complex physical brains trying to navigate an ever increasingly complex physical world. Even today, we have a hard time trying to understand consciousness with our conscious minds.

I think of consciousness as an extension of our early, physical needs and desires. That’s why I think of AI a little bit differently than a lot of people. Many think that AI will be conscious like we are. But AI is something completely different from us, with a different origin and different circumstances. Anything AI becomes regarding love and hate will come from us, as AI will not have evolved needing to reproduce and compete in the same ways we did. If AI doesn’t evolve too quickly and so escape our grasp and understanding, it may be some sort of further extension of our consciousness, as we merge with it. Think of now, how we have cell phones which are extensions of ourselves, and the internet and social media, which are extensions of our existence. We are slowly pouring our consciousnesses into the clouds. Who knows what AI will look like in 100 years, whether we’ll be a part of it, or whether we’ll be blind to that new upper level of the universe.

Ithra: What is your perception of Ithra? How is your Ithra experience going?

DC: Ithra is an interesting place. The architecture is amazing, the details are stunning, and its future is promising. Art in a sense is a new thing here, and Ithra is doing a lot of positive things to help advance the culture. There is a lot of great art here as well. I can’t wait to see the progress in the art scene here in 5-10 years.

Ithra: What is your favorite aspect of the “Direction of Light” project?

DC: The uniqueness of the space where my installation is. It’s a beautiful, minimalistic setting and a prominent location.

- Ithra interview, introduction and images by Daniel Kany