As we welcome Eid al-Adha and plan our celebrations with family and friends, we reminisce on Eid's traditions with prayers and gratitude for all we have. This year, however, with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, Hajj is different. The annual pilgrimage that sees millions gather in Islam's holiest of sites feels like a risk to pilgrims with this infectious disease. Just around 1,000 pilgrims allowed this time for their safety and the safety of their loved ones. Therefore 2020's Eid al-Adha will find a minimal number of Muslims visiting Mount Arafat. Nonetheless, the ritual remains close in people's hearts. For Muslims and non-Muslims, the allure of Hajj is an inspiration.

For non-Muslims to visit one of the world's holiest sites, Makkah and the Holy Ka'ba is an elusive dream and curiosity. Many non-Muslims can only imagine what it would be like. Centuries ago, some even snuck in disguised as Muslims to quench their interests.

Explorers were intrigued by the Arabian Peninsula and imagined what the two holy cities of Makkah and Madinah looked like. They interpreted this imagination into art, and others like Sir Richard Burton returned to their homes with vivid accounts of their visit to the "secret city."

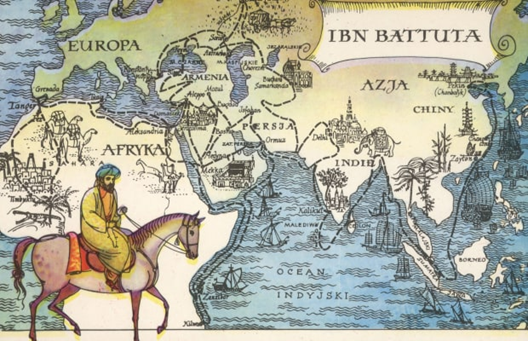

Amongst the many famous travelers and explores who undertook the journey to Makkah for Hajj was Ibn Battuta, a name familiar to many. Ibn Battuta Muhammad Abu Abdullah was born in 1304. He lived a life filled with knowledge-exploration and adventure before he died in 1368. He is a renowned Muslim Berber Moroccan scholar, explorer, and author of one of the most popular travel books, Rihla (Travels). His extensive travels cover 75,000 miles (120,000 km) to almost all Muslim countries, including China. He spent nearly 30 years journeying across the globe, and his journey began when he set off to Makkah to perform his Hajj pilgrimage. During his trip to Makkah, he faced attacks from bandits in the desert and was rescued by Bedouins, and endured intense sand storms. Finally, after 16 months, Ibn Battuta reached Makkah to perform Hajj.

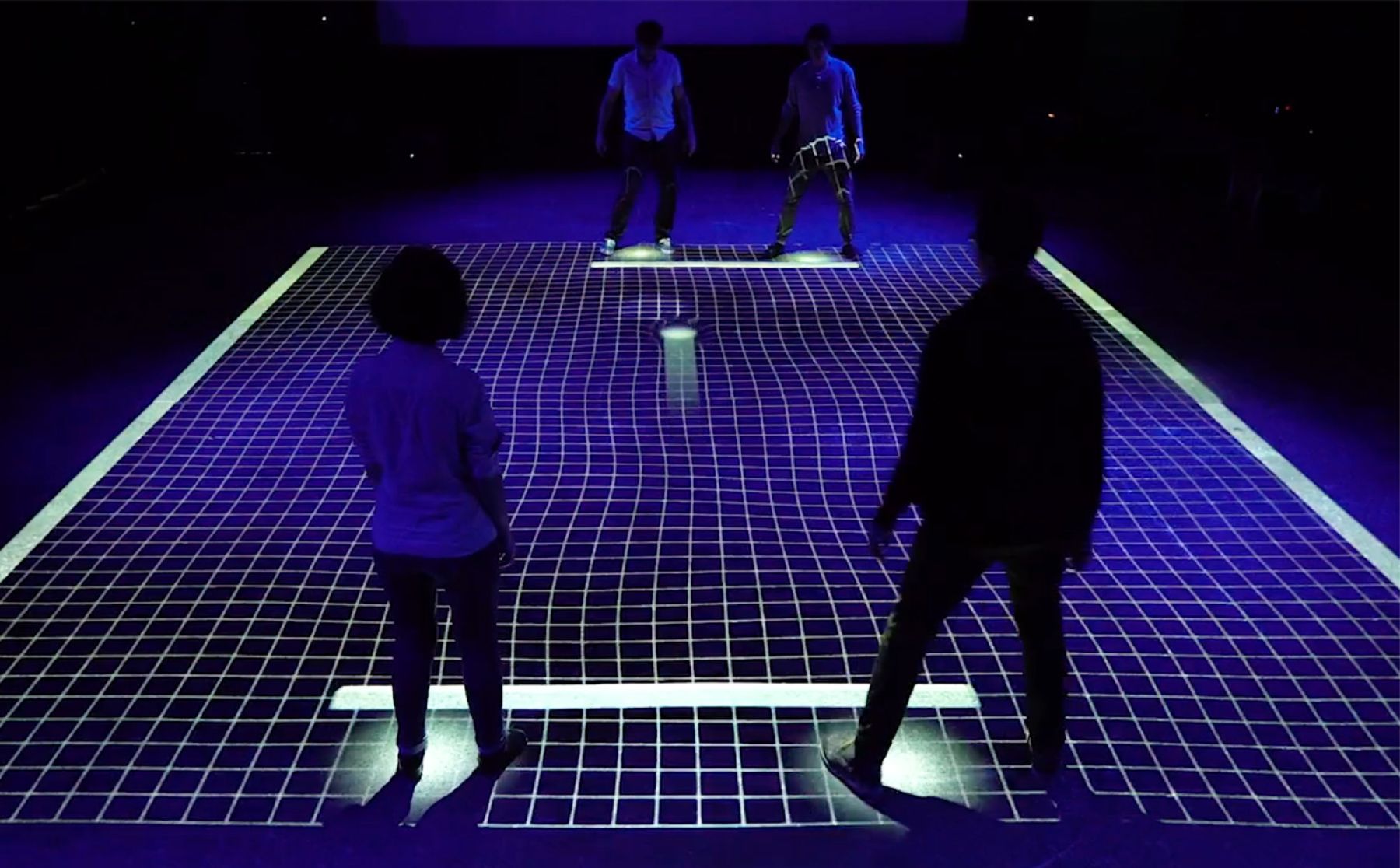

The allure of the Hajj pilgrimage—particularly the mystery behind Makkah—inspired artists and worldview thinkers to capture this ritual in the most creative ways.

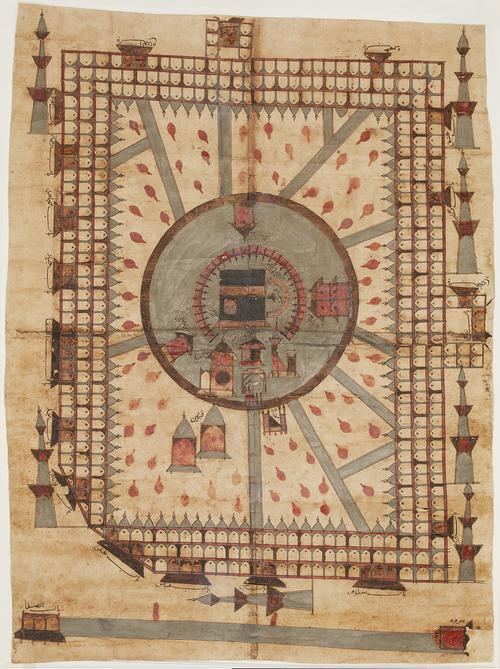

Depictions of the Ka'ba (the House of Allah) were drawn on fabric or paper centuries ago. From the Aga Khan Museum, a bird's-eye view painting on cloth (featured here) presents the Ka'ba at the center. This painting illustrates the House of Allah, mimicking as a pulsing magnet that attracts its surroundings. Before the dawn of photography, Makkah's depictions were treasured souvenirs. They served as a visual illustration of the Muslim holy site.

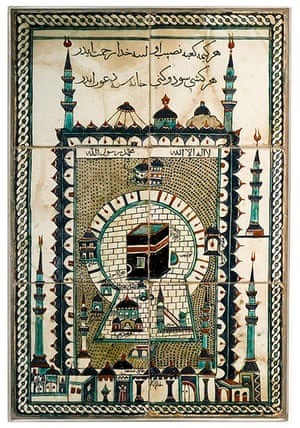

Visual recreations of the Ka'ba have been printed on various types of material. One beautiful illustration of the Ka'ba is one from Iznik, Turkey (featured here). The 17th-century tile illustration shows the House of Allah in the center.

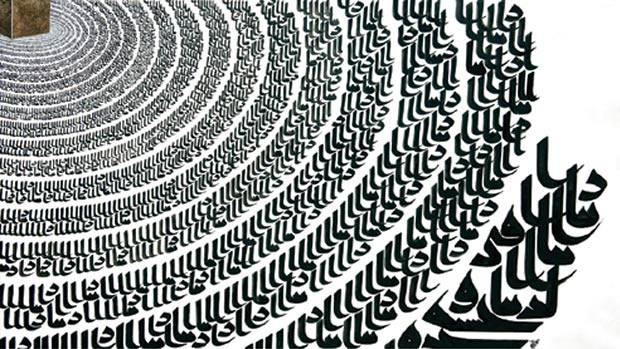

Modern art pieces representing Hajj have been created as a tribute to the wondrous pilgrimage. Azra Aghighi Bakhshayeshi is one particular artist whose work, Tawaf 1 (left), is part of Ithra's art collection and featured in the monthly magazine Ithraeyat. The piece's repetition of the letters creates a meditative rhythm similar to the one felt by pilgrims during Tawaf.

In our modern age, where the quick click of a camera captures what the eye can see, many photographers pay homage to the beauty of Makkah's mystery. One such artist is Princess Reem Al Faisal, the granddaughter of the late King Faisal of Saudi Arabia. Her photo, titled Hajj 127 (left, middle), featured in Ithraeyat and is courtesy from Barjeel Art Foundation, represents Hajj's humanity in an intense situation. Her photograph not only showcases the magnificent pull of Hajj but represents a time that was possibly taken for granted.

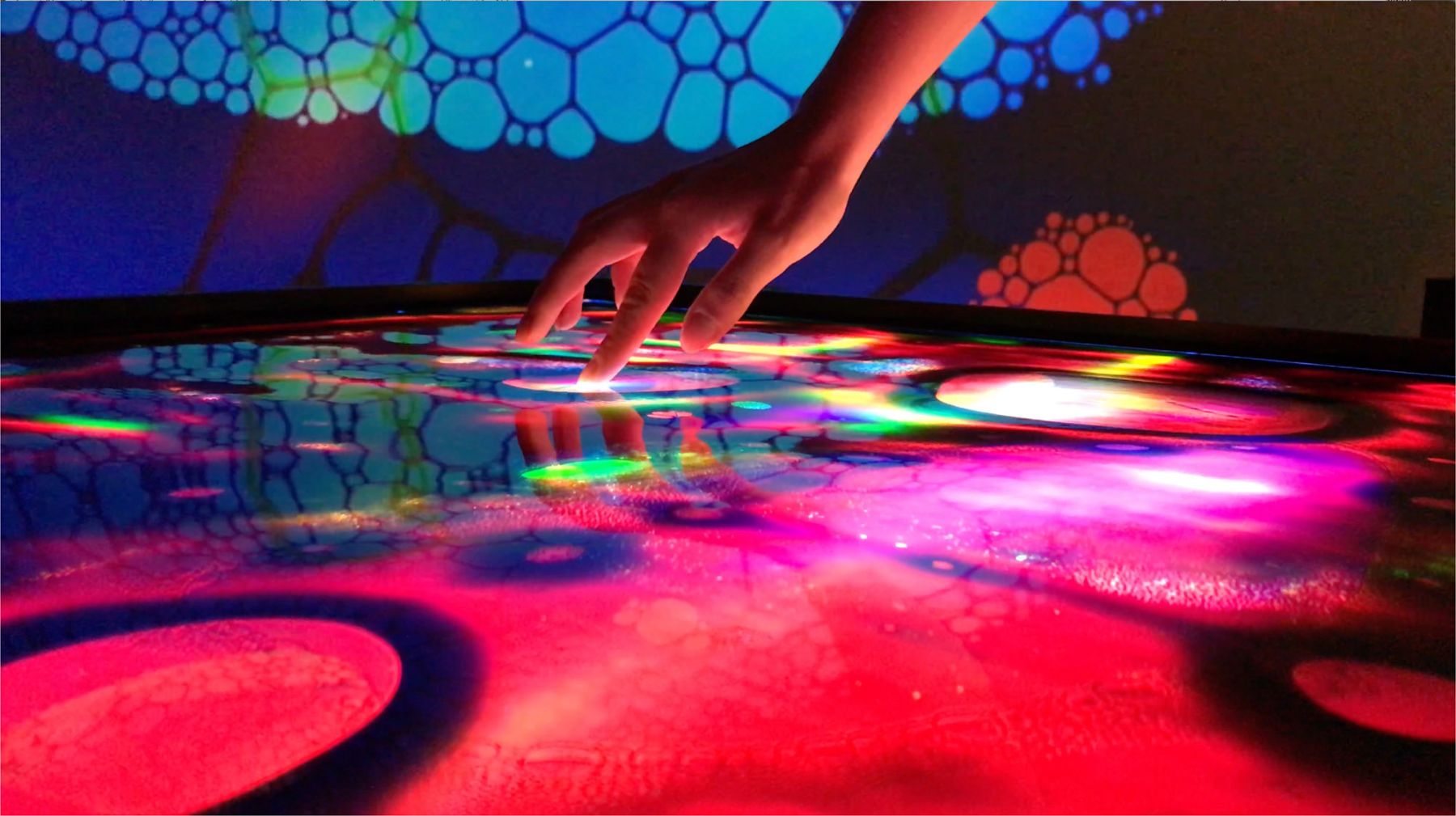

Another renowned artwork that has been popular for its symbolic depiction of Makkah is Ahmed Mater's Magnetism III (left). His representation of metallic filings illustrating the Muslims tawaf circling the Ka'ba. The cube demonstrates the pull of the Hajj pilgrimage in a simple yet powerful way. The journey of Hajj for Muslims is the pivotal point of atonement, a place of safety.

Hajj has been a ‘magnet’ for the curious and the followers of Islam for centuries. It will remain so whether hundreds of thousands crowd its vicinity or just a handful of worshippers visit.

By Nora Al-Taha