For thousands of years, imaginative tales embodied the beliefs, customs and rituals of communities, while they amused, enlightened and instructed their audiences. Oral narratives managed to strengthen communal ties, not only by banishing the monotonous drabness of everyday life, but also by mirroring the collective psyche of human culture. The rich metaphors of the tales open the windows of the imagination and connect people to their surrounding world through group conformity and normative response.

Excerpts from Dr Lamia Baeshen folktales book.

Oral tradition handed down multifarious types of stories; myth, legend,folktale, fable, and fairytale that are often grouped together invariably to mean “old fantastic stories.” But this misconception blurs the differences that distinguish each one of them. A myth is a product of a distant past that is sometimes sacred, it revolves around "larger than life" figures struggling with cosmological issues. Its stories are epical in dimension and intensity, projecting man’s struggle with the forces of nature.

The realm of legends is historical heroism where grand stories are weaved around an inspiring leader, strong enough to win all battles with an evil enemy in long, episodic adventures. And while fables are mainly stories of animals, fairy tales involve fairies, giants, dragons, and other fanciful creatures.

A folktale, on the other hand, contains elements of each type; humans, animals, fanciful creatures, magic, religion, romance, and bravery, but its tone is more realistic and down to earth; it is essentially concerned with issues of everyday life showing conflicts and resolutions. It may deal with matters seriously, but it may also be funny and silly at times. Winston Churchill once said out of intense complexities emerge intense simplicities. If we were to reverse that saying, we would get a perfect definition of a folktale. The simple tales, and their direct colloquial style have a great potential to play a complex role in the celebration and preservation of culture.

It is interesting that nearly all of the tales have parallels in every part of the world, and the question of the origin of these tales is never resolved. This narrative form is living proof that the imagination is the fundamental instrument of rational thinking, and as indispensable imagination is to human cognition, so is the folktale to our literary and cultural constructs.

Since there were as many tellers as there were tales to tell, the stories became individualized and varied and their forms were never stable or complete. Tellers could manipulate the sequence of events, the roles of the characters, and the length of the plot, to formulate their own versions of the same tales. Tales gave utterance to people's culture and value system, to their hopes and fears. Utility and pleasure served, they functioned as a form of moral construction under the guise of playful enjoyment.

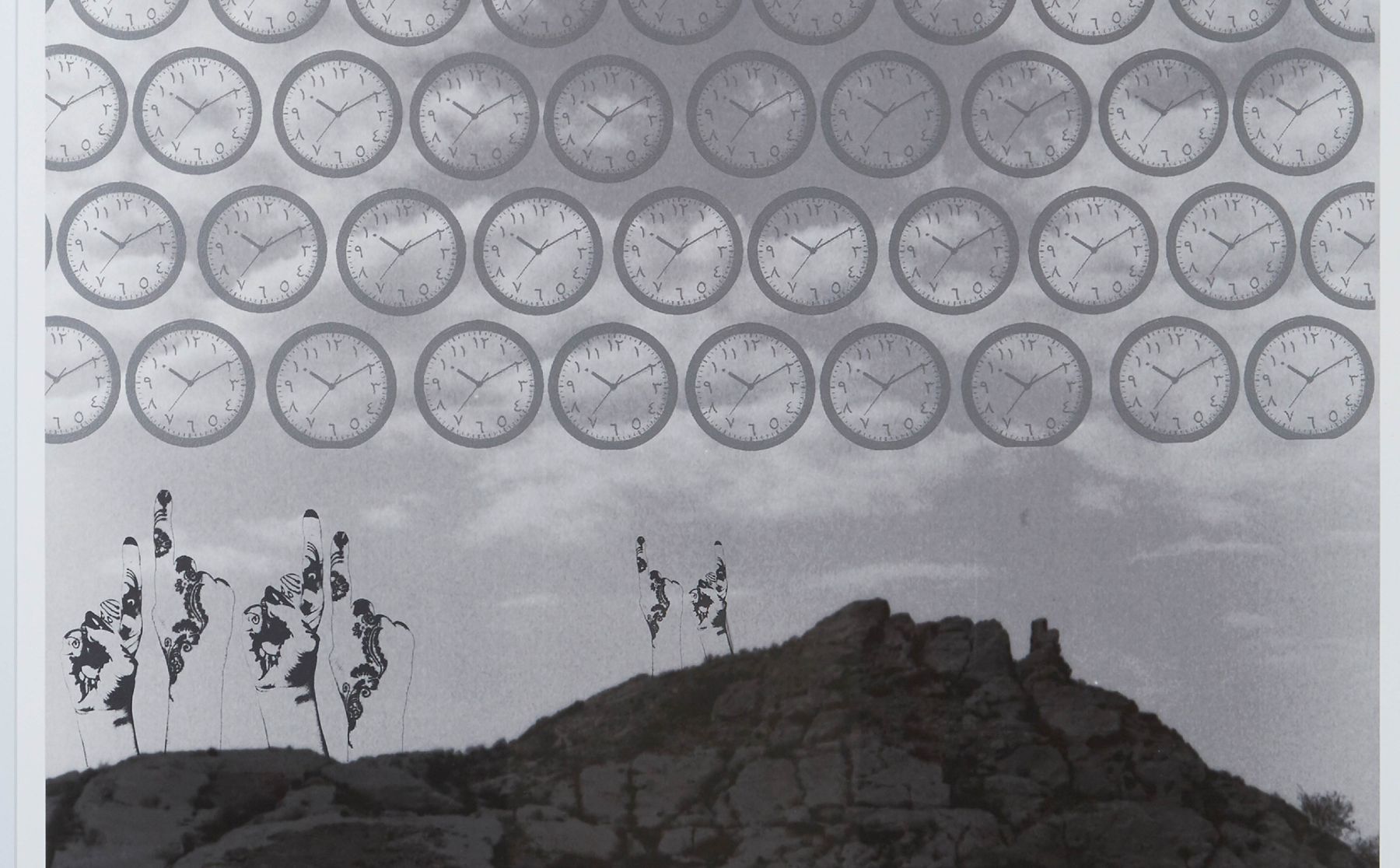

Up till the early decades of the 20th century, the small population of Jeddah had not yet been ushered into the world of the performing arts. In the absence of the theatre, orality was prominent, and people of all ages used to gather for entertainment around one single performer—a hakawati or Rawi (storyteller)— who provided them with a one-man show through the simple act of telling a tale. At night, as children got ready to sleep, they waited anxiously for the aunt, or mother, or grandmother to carry them on the wings of imagination to faraway lands where they would experience fanciful adventures. This ritual of telling tales was a very popular practice in nearly all homes, thus it assisted in shaping identity, moral conduct and social norms.

In my book, titled “Al-Tabat wa Al-Nabat” (which translates roughly to the equivalent “happily ever after”), I have collected traditional Hejazi folkloric tales which were taped as the subjects, mostly older women, were telling them to a live audience. The tales are captured in their original Hejazi dialect to present in this book the dynamic essence of the wealth of folkloric material which I was lucky enough to save from extinction, for the art of telling tales is nowadays a thing of the past.

One distinct feature of Hejazi folktales that appeals to me is the presentation of women as heroines: females in general appear as strong women in roles of power and moral authority who overcome challenging situations and always win by applying their wit, wiles and perseverance. In the tale of “Pearl, the Daughter of Coral,” which resembles the story of Rapunzel, the symbolic power of Lulwa’s long hair is equally matched by her sturdiness and power of mind. Just like a pearl that is hidden in a secured place, isolation makes her stronger and she succeeds in her battle with the imprisoning witch. Similarly, the girl in “The Bone” tale fearlessly breaks out of the underground cell her father kept her in, preferring her freedom and independence to the safety of the shackles of her home.

Sometimes young women venture out on missions to save men from hardships, like the heroine of the tale “the Bird of Happiness.” When many brave men seek that bird but fail to capture it, this young woman rises to the occasion and passes the test so brilliantly that she not only captures the bird, but also frees all the men who were turned into stones. In the tale of “the Gardener’s Daughter,” the gardener is challenged by the Sultan to solve a series of difficult riddles, he goes home to his daughter sad and distressed, for there seems to be no exit from his dilemma, but the smart girl surprises him with one answer after another, until the Sultan finally pardons him.

The real charm of the simple folktale is truly revealed through reading between its lines and contemplating the wisdom of the messages it carries within. My dream is that preserving these Hejazi tales, which provide merely the crude matter of the whole narrative art, would revive the genre of the folktale so people can cherish their own heritage and begin to pass it on to future generations.

Special Guest Columnist:

Dr. Lamia Baeshen is a Saudi scholar, critic and author specialized in folktales and oral heritage. She is also a professor of Literature at the Department of European languages and literature at King Abdulaziz University in Jeddah.