“Arabic calligraphy is music for the eyes….”

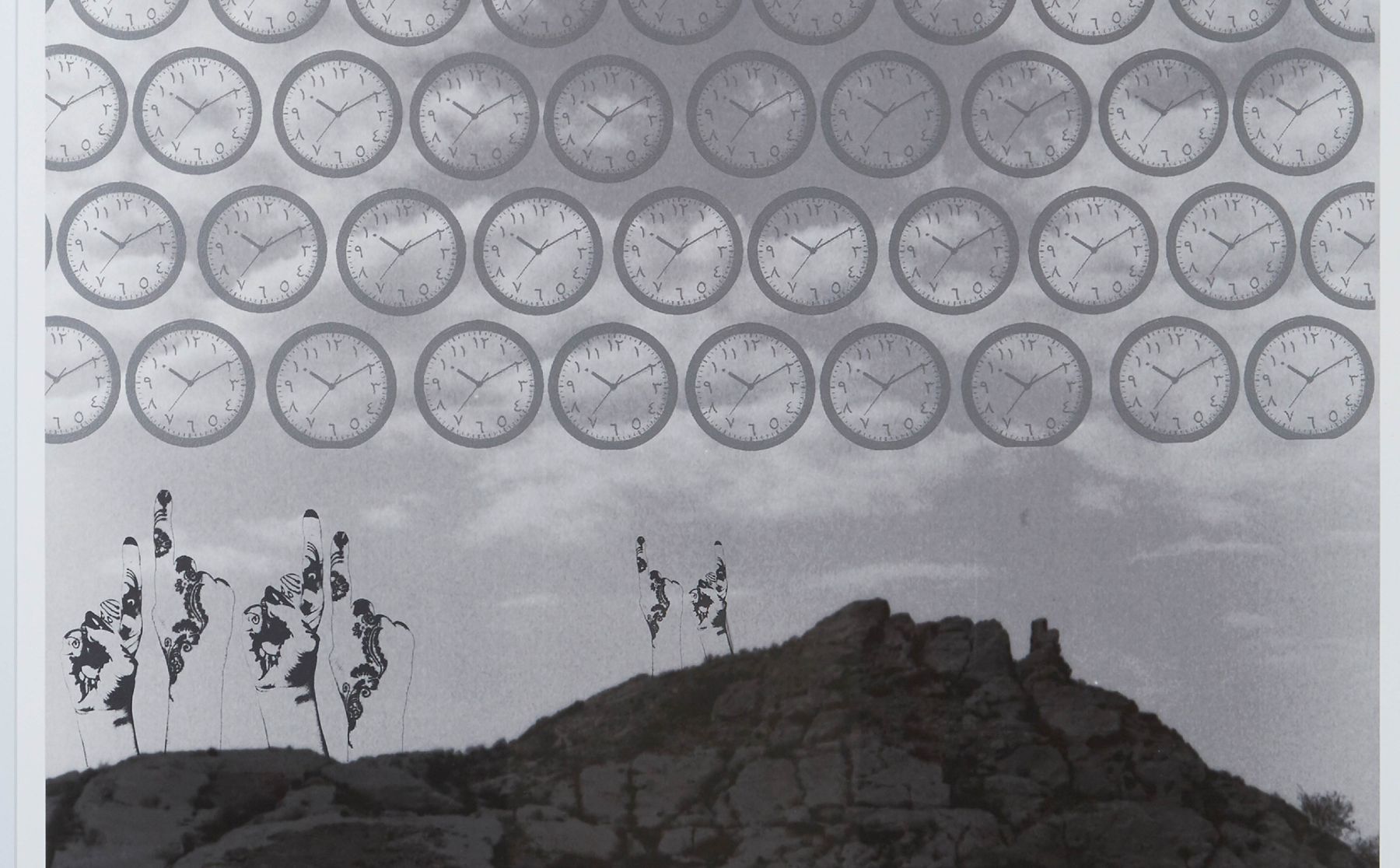

For the past 15 years, Abdulrhman Al-Faiz has been capturing and recapturing the beauty of the past and present, the classic and the contemporary, in one of the Arab world’s most divine arts: calligraphy.

"How someone expresses themselves in calligraphy tells me a lot about their personality and psychology," he said. "In some ways, calligraphy is a mirror of the soul.”

From Al Khobar, currently living in Riyadh, Abdulrhman is a contemporary artist and Arabic typographer whose journey into calligraphy began with his father.

“I was about 10 years old and one time, my father asked to see my homework. He saw how atrocious my handwriting was, and so he ripped the notebooks and asked me to start over. He has beautiful handwriting. He wrote me one sentence that I had to trace,” he recalled.

“Ever since then, I started to notice writings, and I would enjoy for instance reading funeral posts, as they were often written beautifully in different forms of calligraphy.”

In honor of his late father, whose name was Faiz, he uses it as a last name.

“It is thanks to him I noticed that writing is an art, it is not just a means of communication. It is a bit of identity, a bit of spirituality, a bit of art and a bit of expression,” he said.

A power technician by study, Abdulrhman started his personal self-learned journey of calligraphy by studying it with a friend in his neighborhood, Yahya Nouh, who had passed away due to an accident.

“There were several who have helped me reach where I am. Some encouraged me with a word, others like Yahya, we learned together how calligraphy is more of a spiritual nourishment for calligraphers.

There is a lot of study, memorizing writing rules and guidelines, experience and practice,” he said. Abdulrhman has managed to become an expert on both classic and contemporary Arabic calligraphy, and has managed in his art to become a bridge between the two. “I research and rediscover rare calligraphic forms and revive them in my art,” he said.

For the cover of the current issue of Ithraeyat, Abdulrhman chose a rare Kufic form, an ornamental one, often found in the divider section of the Qur’an.

“In the bounty of Allah and in His mercy - in that let them rejoice; it is better than what they accumulate.” (Qur’an 10:58)

“I took the word Falyafrehou, let them rejoice, and reimagined it as a celebratory word that we should all live by,” he said.

Another interesting point noted by Abdulrhman is how in the Arabic language there are many words that mean ‘joy.’ “There is just a wider range of depth in Arabic, and so the art of calligraphy and expression is boundless,” he said.

A project dear to his heart, ‘Amshaq’, an online resource that he set up with two calligrapher friends, where they would provide the tools, books and courses needed to help aspiring calligraphers across Saudi Arabia. “It was a kind of a revolution, where before a calligrapher had to order their tools from Iran or Turkey, our corporate social responsibility project helped inspire other companies to provide what a calligrapher needs,” he said.

Arabic Calligraphy: Its many faces

Derived from the Greek word kallos (beauty), calligraphy means “the art of beautiful handwriting.”

Following the oral tradition of the language, Arabic calligraphy emerged in the first century of Islam, about 622, and has continued to evolve throughout the ensuing centuries.

Calligraphers would compete among themselves and use the most beautiful and creative form of calligraphy when writing and copying the Holy Qur’an.

There are several notable forms. There is the Kufi, that was used to write the first copies of the Holy Qur’an and is the oldest form of calligraphy, dating to the early 7th century.

Many modern Qur’ans are written in Naskh, a more cursive style dating to the late 8th century that is easier to read.

While Thuluth is a script that appeared in the late 9th century and mainly used in ornamental scripts like titles, headings and colophons, Thuluth al Jely is a classical script and one of the most important and difficult to write and read.

Ruq’ah, which means small sheet, has been revised over the centuries and simplified to become the most commonly used font in the Arab world.

“Arabic calligraphy proliferated with the spread of Islam as it was used to write out the Holy Quran” said Abdulrhman. “Calligraphy absorbs the culture and identity of its origin since ancient times.”

Every country is distinguished by certain types of calligraphy. The early days of Islam and the Umayyad era, for example, were characterized by the Kufic script. Lean scripts, such as tumar and al-thuluthain began gaining wider interest in later periods.

Persia, on the other hand, excelled at and adopted the ta’lik script. It inspired another script adopted in Persia called the shaksta, which had a different structure and rhythm than ta'lik though the same spirit and origin.

The art of calligraphy intersects with architecture, printing, furniture, and clothing; comprehensive design he explains.

“It is one of the most revered and spiritual art forms, one that keeps expanding and challenging the artist and the viewer.”

To discover more of Abdulrhman Al-Faiz’s dynamic art, please click here.

Written by Rym Tina Ghazal