The Teardrop on the Cheek of Time and the Nostalgia of the Heart

“You know Shah Jahan, life and youth, wealth and glory, they all drift away in the current of time. You strove therefore, to perpetuate only the sorrow of your heart. Let the splendor of diamond, pearl and ruby vanish. Only let this one teardrop, this Taj Mahal, glisten spotlessly bright on the cheek of time, for ever and ever.”

—Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) Indian poet and winner of the 1913 Nobel Prize for Literature

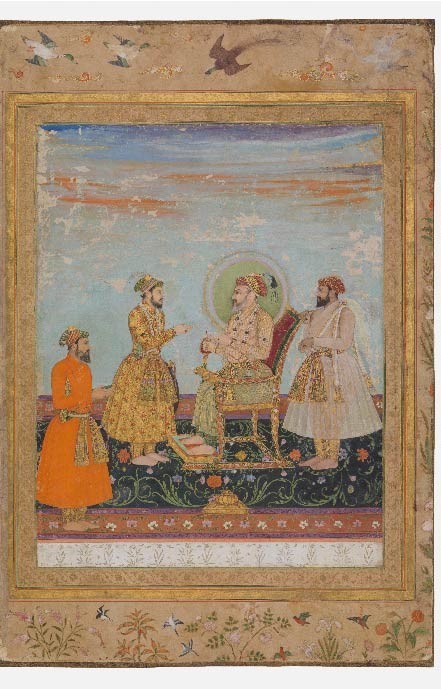

“A Folio from the late Shah Jahan Album. India, c. 1650 Opaque watercolor, gold, and ink on paper 37.2 × 25.4 cm. From the collection of Nasli and Alice Heeramaneck, New York: acquired by LACMA in 1983.

Everyone loves a love story. They have been watched, read, heard and dreamt about, with first loves often holding a very special place in the heart. Love songs trigger memories, and leave the mind wandering and the heart longing. One such love story that continues to touch the hearts of its visitors is that of the iconic sublime shrine to eternal love: the Taj Mahal.

A UNESCO world heritage site, this immense mausoleum of white marble, was built in Agra, India between 1631 and 1648 by order of a heartbroken Mughal emperor Shah Jahan (reign 1628-58) – “the King of the World – in memory of his favorite wife Mumtaz Mahal.

Theirs was an extraordinary story of passionate love: Mumtaz followed her husband on every military campaign and bore him 14 children before dying in childbirth. Grief driven, his obsession drove him to build the Taj Mahal, which took almost 20 years to construct and depleted the Moghul treasuries. Shah Jahan ended his days imprisoned by his own son in Agra Fort, gazing across the river at the timeless monumental pearl of his love, one he could never visit again.

While most have seen the structure, here we share a rare depiction of the man behind the legend, a miniature dated 1650 from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) collection and exhibited at Ithra.

In it, Shah Jahan is receiving his son Dara Shikoh, Mumtaz Mahal's eldest son. Like most portraits of the famed Mughal ruler, this example depicts him in profile framed by a halo, wearing an extraordinary number of oversized jewels, including pearls, emeralds and rubies, and receiving supplicant courtiers and his children. Two exceptional components of the painting are the European-style chair with armrests terminating in lion heads, and the carpet with a rich black background. Within its original context, the portrait was mounted in an album facing a similar depiction of Shah Jahan’s father, Jahangir (reign 1605–27). Viewed together, the two paintings were powerful visual statements of Mughal dynastic continuity and strength.

In this special issue dedicated to nostalgia, we pay homage to love, to landmarks that remind us of love, to tears shed over memories and stories of the heart.

Written by Rym Tina Ghazal